These words are from the preface to Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass (1855).

I knew a man whose life embodied these words. I called him Uncle Ted.

Rozsa’s weekly book excerpt

Uncle Ted (2006) by Rozsa Gaston

a short memoir

Our next door neighbors on West Hill Drive, in West Hartford, Connecticut, where I grew up were the Littles. There were five Little children, Mr. and Mrs. Little, and their golden retriever, Penelope.

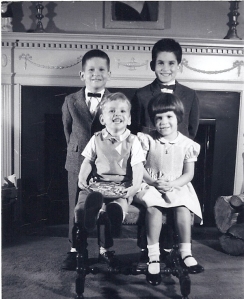

I called Mr. and Mrs. Little Uncle Ted and Aunt Sharon. This is due to the fact that they accorded me privileges of a family member, such as barging into their house through the kitchen door without knocking. I don’t think any of the other neighborhood children enjoyed such a privilege. I lived with my grandparents next door as an only child, and Uncle Ted and Aunt Sharon more or less treated me as their sixth child, so that I could enjoy pretending the five little Littles were my brothers and sisters.

Uncle Ted in particular was the Little I most loved. He ended up being my role model for the ideal man, although I don’t think he ever knew this.

Uncle Ted in particular was the Little I most loved. He ended up being my role model for the ideal man, although I don’t think he ever knew this.

Uncle Ted was both gentle and genteel. He had a soft voice and referred to us children as “laddies and lassies.” I don’t think I ever heard Uncle Ted raise his voice to any of us. I certainly heard Aunt Sharon raise her voice to her children many times; mostly for good reason.

Uncle Ted worshiped Aunt Sharon. There was a painting of her hanging in their living room, which he had commissioned on the occasion of their marriage, when she was 26 years old. She had fluffy, long golden hair and the bluest of blue eyes. Her cheeks looked like apples. It turned out that their youngest child, Rebekah, ended up looking almost exactly like her mother, although all four of the older ones resembled their father more.

My grandmother would pooh pooh the fact that Uncle Ted was so solicitous of Aunt Sharon, but I knew this was only because she was envious of the attention he paid her unfailingly, even after five children and many years of marriage. It was quite remarkable, and after six and a half years into my own marriage, I now realize how completely outstanding it was. Uncle Ted was the husband that every woman should be so lucky to find and keep forever.

My grandmother would pooh pooh the fact that Uncle Ted was so solicitous of Aunt Sharon, but I knew this was only because she was envious of the attention he paid her unfailingly, even after five children and many years of marriage. It was quite remarkable, and after six and a half years into my own marriage, I now realize how completely outstanding it was. Uncle Ted was the husband that every woman should be so lucky to find and keep forever.

Uncle Ted and Aunt Sharon would enjoy cocktail hour in their living room every evening. This was a WASP institution that I admired as a child and enjoy even more as an adult. They would have some cheese and crackers laid out on a platter, and would sit down and enjoy a drink together. The cardinal rule of this cocktail hour was that the children were to behave and show good manners with quiet voices if they wished to join their parents in the living room at this time.

This was a difficult feat to accomplish for five children all very close in age. There were two entries to the living room, one on either side of the living room couch upon which Uncle Ted and Aunt Sharon would sit. The children would whoop, yell and rampage outside the living room, which their parents would pretend not to notice. However, the moment any one of them entered the living room, they slowed down, pulled out their drawing room manners, and practically tiptoed over to the coffee table to take a cracker or piece of cheese. They would then politely slink out of the living room by the other entryway, and within seconds turn into wild Indians again, usually engaged in pursuit or torture of a younger sibling.

Occasionally one or more of the children would forget to put on their drawing room manners upon entering the living room, in which case Uncle Ted or Aunt Sharon would quickly remind them to adjust their attitude. Uncle Ted would say something like, “Slow down there, laddie, don’t disturb your mother,” in a quiet, gentle voice. Aunt Sharon would say something along the lines of, “Put that cracker down RIGHT THIS SECOND and go wash your hands before coming back!!”

While the children were rampaging about the rest of the house like whirling dervishes, Uncle Ted would get up every five seconds or so to tuck a throw or shawl around Aunt Sharon’s shoulders, or ask her if she were warm enough, cool enough, comfortable enough, or would like her drink refreshed. (In WASP households, one does not offer “another drink.” One offers to “freshen” someone’s drink.) He would say, “Are you warm enough, darling?,” or “Can I get you something, darling?”

Uncle Ted was the first man I knew who called his wife “darling.” I had heard this expression by watching lots of old movies with my grandmother, but had not come across it in our particular household. Because of the fact that Uncle Ted called Aunt Sharon “darling,” I now refer to my own husband by the same term. Our six year old daughter has picked it up too, and sometimes calls to her father saying, “darling” (as in “darling, come here, I need you to do something for me…”)

Uncle Ted was the first man I knew who called his wife “darling.” I had heard this expression by watching lots of old movies with my grandmother, but had not come across it in our particular household. Because of the fact that Uncle Ted called Aunt Sharon “darling,” I now refer to my own husband by the same term. Our six year old daughter has picked it up too, and sometimes calls to her father saying, “darling” (as in “darling, come here, I need you to do something for me…”)

Uncle Ted’s version of “darling” was not a need-based term, but rather a beautiful present that he offered his wife again and again through all the years of their marriage. His terms of endearment and frequent solicitations were his way of saying thank you for being my wife and for having five of my children in the space of eight years. At the rate that Aunt Sharon had churned out children, she was entitled to a little solicitation which Uncle Ted generously gave her.

My grandmother loved both Uncle Ted and Aunt Sharon dearly. However she would sometimes imply that Uncle Ted was a bit of a pushover or a “softie.” Even at a very young age, I could see through her criticisms and knew she was simply jealous of the fact that Uncle Ted took such good care of Aunt Sharon. To this day I have always been attracted to gentle and genteel men, and I have Uncle Ted to thank for this.

My grandmother loved both Uncle Ted and Aunt Sharon dearly. However she would sometimes imply that Uncle Ted was a bit of a pushover or a “softie.” Even at a very young age, I could see through her criticisms and knew she was simply jealous of the fact that Uncle Ted took such good care of Aunt Sharon. To this day I have always been attracted to gentle and genteel men, and I have Uncle Ted to thank for this.

Uncle Ted (2006) by Rozsa Gaston